Bristol: City of Sanctuary?

In 1992, I was filming a documentary for the BBC in Diyarbakir, southeastern Turkey. I stood on a rooftop, capturing scenes of Kurds dancing in celebration of Newroz — the festival marking New Year and the arrival of spring. It was a moment of joy for an ethnic group long denied cultural rights and autonomy.

But within minutes, the mood shifted. Turkish police charged through the narrow streets below, shields raised, batons swinging. They stormed the celebrations and made arrests.

For me, it was a stark insight into why some people feel they have no choice but to flee their homeland in search of safety. Some Kurds — from Iran, Iraq, and Turkey — have done just that, and made their way to Bristol. Alongside other refugees escaping war, persecution, and political oppression.

In 2012, Bristol became a ‘City of Sanctuary’ — part of a UK-wide movement to build a culture of welcome for those seeking refuge. It’s a grassroots commitment by local institutions not just to offer support, but to challenge hostility and misinformation around asylum.

Reform UK — a party vowing to resist housing people seeking asylum — is gaining ground. Their West of England mayoral candidate, Aaron Banks, came a close second in May’s election.

At Bristol Refugee Rights, where I volunteer, we had to cancel a seaside trip last year, fearing violence after the racist riots of 2024. Funding is a constant struggle. BRR had to shut down both its crèche and English programme in 2023 due to lack of funds.

And yet, Reform UK continues to rail against the “failure” of refugees to integrate — while the city denies many the most basic tool for doing so: the chance to learn English.

More than a decade on from Bristol becoming a City of Sanctuary, are we still living up to that promise?

Resisting racism

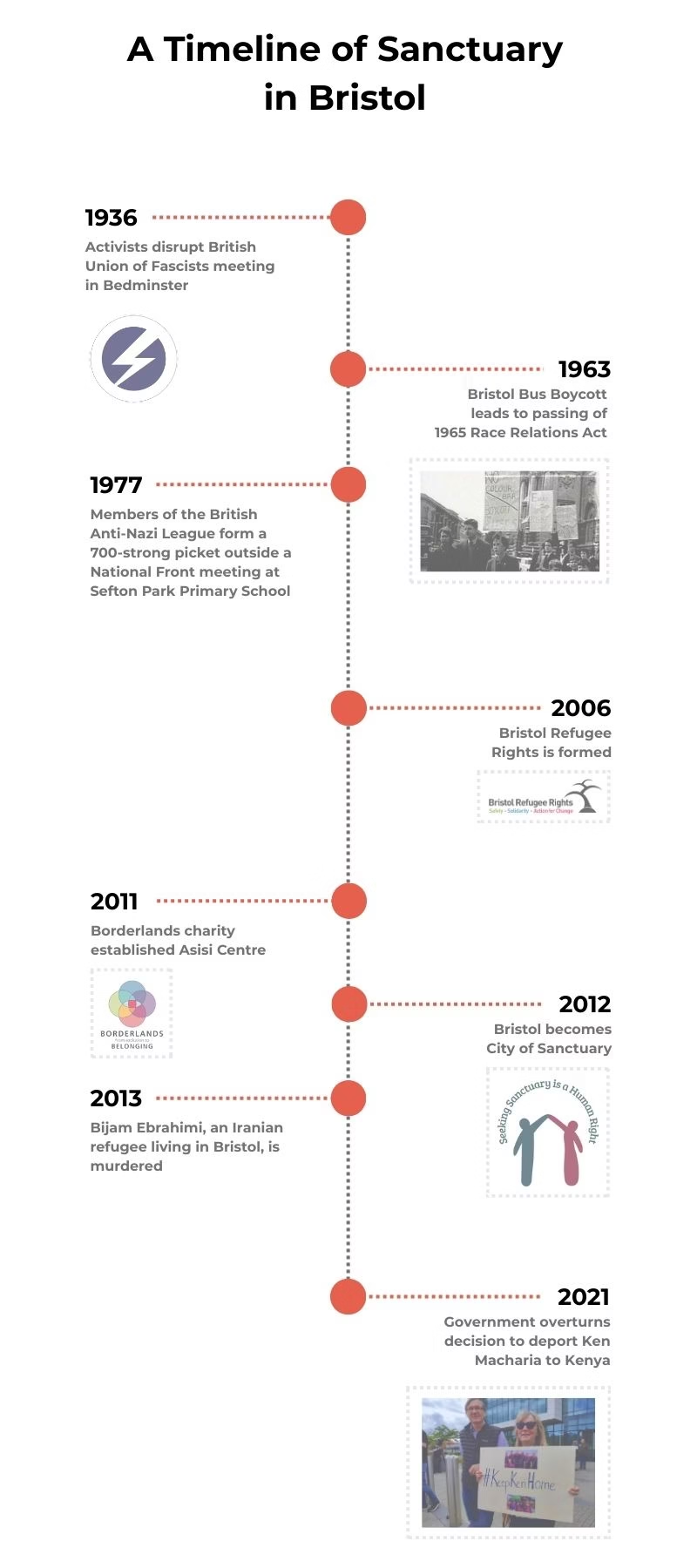

Bristol has a long history of bigots stirring up hostility to new arrivals — and of people pushing back. When the British Union of Fascists (BUF) held a meeting in what was then Colston Hall in 1936, they were heckled and confronted by anti-fascists. When the BUF’s leader, Sir Oswald Mosley, tried to speak in Knowle West’s Melvin Square, members of the Labour and Communist Parties physically attacked him.

The city gained national — and more recently international — recognition for the Bristol Bus Boycott of 1963, a landmark stand against racist hiring practices that helped pave the way for the Race Relations Act of 1965. The far right saw those measures as defeats. In response, In 1967, the National Front (NF) was formed, hoping to capitalise on anxieties about immigration.

Though its early electoral support in Bristol was minimal, the NF seized on the arrival of 27,000 Ugandan Asians in 1972 — forced out by General Idi Amin — to stoke tensions. The NF grew locally, prompting frequent physical confrontations with anti-fascist groups.

In 1977, left-wing activists mounted a 700-strong picket at an NF meeting at Sefton Park Primary School. Police arrested six picketers. A year later, Bristol anti-fascists formed a local branch of the Anti-Nazi League (ANL), which directly challenged NF activity, ready to confront fascism in the streets.

But many refugees still faced racism alone. Zara Haq, a Pakistani woman born in Singapore who arrived in Bristol in 1977 and became a prominent community activist, recalls that Asian women in Barton Hill “didn’t feel comfortable because racism was rife at that time.”

New initiatives

It wasn’t until 2006 that an organisation was set up specifically to defend the rights of refugees and people seeking asylum: Bristol Refugee Rights (BRR) – a group whose very name was a challenge to the political climate of the time.

Bristol has a long history of bigots stirring up hostility to new arrivals — and of people pushing back.

In the years that followed, new initiatives emerged. In 2010, the Bristol Hospitality Network began offering accommodation to those left in limbo by the asylum system. A year later, Father Richard McKay founded Borderlands at the Assisi Centre in Easton, creating a safe and welcoming space for sanctuary seekers.

That same period saw veteran journalist and historian Mike Jempson launch The Bristol Globe, a magazine that offered “a warm welcome to those who come and live here, and a reminder to the rest of us about where we come from and what we can offer each other.”

In 2012, Bristol formally became a City of Sanctuary, pledging to offer safety to those fleeing persecution and war.

But just a year later, the brutal gap between aspiration and reality was laid bare. While Bristol’s history of resistance has shaped its identity as a place of sanctuary, the lived experiences of refugees often reveal painful contradictions.

Persecution and protest

Bijan Ebrahimi, a disabled refugee who had been tortured in Iran, was living in south Bristol. His neighbours falsely accused him of being a paedophile. Despite repeated pleas for help, police ignored him. In July 2013, he was murdered in a vigilante attack: beaten, stabbed, and his body set alight. Two officers were later jailed for misconduct in public office.

In 2018, when the Home Office detained Ken Macharia, a Kenyan refugee and mechanical engineer, Bristolians showed that the City of Sanctuary label still had power. Macharia, a gay man, faced deportation to a country where he would likely face persecution. He was a much-loved member of the Bristol Bisons, an inclusive rugby team. Protests erupted — from teammates and across the city — and in 2021, the decision was overturned.

Some of the Kurds I met through BRR have flourished in Bristol. Bnar, who grew up in Iraq, just graduated with a first in photojournalism from Cardiff University. Nabil, also from Iraq, exhibits his artwork at the Royal West of England Academy and performs with the Dovetail Orchestra. Sama, once threatened with execution by Iranian police, now runs the popular Sam’s Master Grill on Cheltenham Road.

There are now dozens of support organisations for refugees and people seeking asylum in Bristol. But the situation remains precarious. The city’s promise of sanctuary clashes with ongoing challenges — from underfunded services to rising political hostility. The fight for a true welcome demands ongoing commitment.

Colin Thomas is the author of City of Sanctuary?, a pamphlet produced by the Bristol Radical History Group. Available for £3 at brh.org.uk/site/pamphleteer.

Independent. Investigative. Indispensable.

Investigative journalism strengthens democracy – it’s a necessity, not a luxury.

The Cable is Bristol’s independent, investigative newsroom. Owned and steered by more than 2,600 members, we produce award-winning journalism that digs deep into what’s happening in Bristol.

We are on a mission to become sustainable, and to do that we need more members. Will you help us get there?

Join the Cable today